STAGE 1, CONCEPT 1 | Table of Contents

The Eviction Crisis

Eviction RTC laws are an important piece of the puzzle in addressing the national eviction crisis. In this section, we explore the current eviction landscape around the country, provide an overview of the eviction process (including how not having a lawyer comes into play), and outline the common consequences of eviction.

The Eviction Crisis in the U.S.

“EVICTIONS ARE HARMFUL for everyone involved. Landlords and tenants both want stability in housing arrangements. For landlords, the process of eviction and finding new tenants is costly. For tenants and their families, the costs are even higher: A forced move may mean the loss of their security deposit and belongings, a change in schools, a longer commute to work, and a negative mark on their rental history that can make finding suitable housing more difficult. For some tenants, eviction will result in homelessness. Finding ways to increase housing stability by resolving disputes between landlords and tenants benefits everyone.” - Eviction Prevention Report, Hawaii

We’re working toward a future where everyone has a safe, permanent, affordable place to call home that they don’t have to fight for. Evictions are contrary to that goal. They have been and continue to be a driver of housing instability and homelessness. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 3.6 million “formal” eviction filings per year, meaning evictions where the landlord served the tenant with court papers. While the filing numbers were lower during the height of the pandemic due to laws temporarily prohibiting landlords from evicting tenants, the eviction filing rates have since rebounded and in some cases exceeded the rates prior to the pandemic.

But the filing numbers only scratch the surface of the eviction crisis: studies have shown there are at least five times as many Informal or Illegal evictions, which are situations where landlords evict tenants without using a court process. Children are by far the most impacted: a recent Eviction Lab study found that “The average eviction case filed in America involved roughly one child under age 18. Children were present in 52.2% of renter households filed against compared to only 33.5% of renter households not filed against.”

“Structural racism and discrimination result in housing instability for many Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) communities by limiting opportunities for quality employment, affordable homeownership, and access to other means of building wealth and economic stability; forcing many Black and Latine households to live in unsafe housing; and driving eviction and health disparities.” (Advancing Racial and Health Justice Through a Right to Counsel for Tenants, 2024)

Worsening the problem is the fact that the country’s housing and court systems have been shaped by racism and racial bias, and this is reflected in the most recent research about who is threatened with eviction and facing eviction the most:

“Non-Hispanic Black renters were the only race/ethnicity group overrepresented in eviction filings and judgments…Overall, Black Americans made up only 18.6% of all renters yet accounted for 51.1% of those threatened with eviction and 43.4% of those who were evicted. By contrast, although White Americans make up just over half of all renters (50.5%), they accounted for only 26.3% of those threatened with eviction and 32.0% of those who were evicted.”

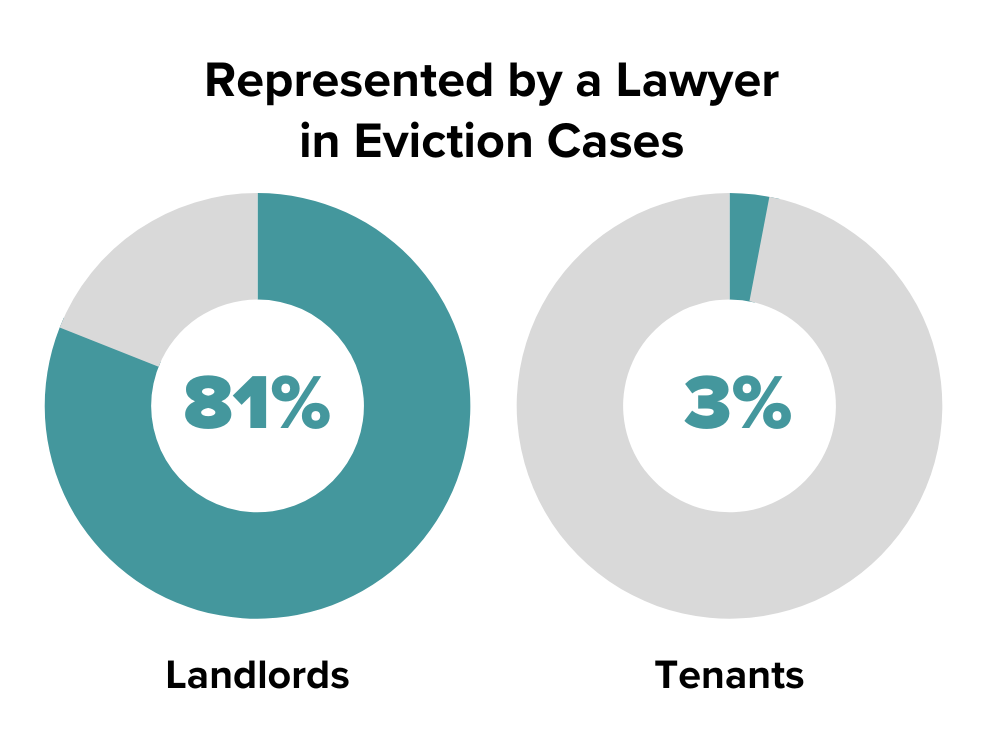

Against this backdrop, most tenants go through the eviction process without a lawyer. While past reports often said that 10% of tenants have representation, our eviction representation data shows the actual figure is 4% on average. That means that 96% of tenants on average, the vast majority of which have no legal training or knowledge, face eviction alone. Meanwhile, landlords on average are represented 83% of the time on average.

Looking deeper at the data.

Comparing data across jurisdictions, particularly when looking at representation rates of landlords and tenants, can be difficult: words can have different meanings in different places. For instance, in some states the landlord representation rate includes landlords represented by a non-lawyer agent because the law in those states allows it, whereas in other places the only person that can represent a landlord is a lawyer. It’s worth noting that while landlord agents are not lawyers, they have much more knowledge and understanding about evictions than the tenants due to either training or having handled many evictions.

Why are eviction filing rates so high right now?

There are many reasons for the high number of eviction filings across the country, including:

Superheated rental markets, where landlords have more incentive to evict tenants;

An ever-growing gap between wages and rent prices; and

The end of most pandemic protections (eviction RTC is one of the few that has lasted) and federal rental assistance.

But also, filing rates before the pandemic (3.6 million a year ) were already really high. It’s just that many people weren’t aware of that until the pandemic raised the visibility of evictions.

The Process of Eviction

In this section, we cover issues that can come into play when a tenant has to proceed through this process unrepresented.

NOTE: This section describes the eviction process generally, not how it works in each particular state, and is not legal advice. If you are interested in learning more about the eviction process in your state, we encourage you to visit the LSC’s Eviction Laws Database and connect with an experienced housing attorney in your area.

Step 1: A landlord-tenant contractual relationship is formed.

To rent a home, a tenant enters into a written or oral lease with a landlord or landlord’s agent. Landlords can refuse to rent a property to a tenant for any reason except for certain types of discrimination covered by the federal Fair Housing Act (or state law equivalent) or for reasons prohibited by state or local law (for instance, some cities and states prohibit landlords from refusing to rent to a tenant on the basis that the tenant has a Section 8 voucher).

In other business situations, including commercial leases, the terms of a contract are negotiated between the two parties, but this rarely happens for residential rentals unless the tenant has choice, time, and money. And even then, if there is a lot of demand for the housing, landlords have little motivation to make changes to the lease. In situations where a tenant is dealing with an unaffordable rental market, relying on a housing subsidy like Section 8, has any kind of criminal record, or has a negative rental history (like a prior eviction), their negotiating power is near zero.

Leases are not forms that are created by the government; they are written by landlords. Some landlords use cheap, standardized lease forms downloaded from the internet that may not comply with state or local law. A 2021 study of 170,000 leases linked to 200,000 Philadelphia eviction cases between 2005 and 2019 found that “the incidence of both unenforceable and oppressive terms has sharply increased over the last 20 years.” One of the study’s authors suggested that leases with these kinds of clauses can lead to informal evictions: “Most of the time tenants leave their premises, it’s not because they’ve been evicted through court proceedings, it’s because the landlords have basically found private ways to force them out…[i]t might be that landlords are convincing tenants that they don’t have the rights that the law actually gives them.”

A landlord can include anything in the lease that the state and local landlord/tenant law doesn’t prohibit. For example, according to the LSC’s Eviction Laws Database, nine states allow the landlord to include a provision in the lease that a tenant who signs the lease waives their right to notice of an eviction. However, some states may have laws that limit the landlord’s ability to set certain terms: for example, rent stabilization laws set a limit on rent increases, while some states prohibit leases that waive certain tenant rights (like the right to safe housing or the right to a jury trial in an eviction case)

Landlord-tenant laws can be changed. Many landlord-tenant laws focus on protecting private property rights and thus favor the landlord as the property owner. But advocacy can and has made better laws! For example, advocates in NYC reshaped the law to be more rights-protective with the passage of the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act of 2019. Advocates in Washington State achieved additional tenant protections in 2023.

Step 2: At some point during the tenancy, the landlord decides to evict the tenant.

If a landlord decides they want to remove a tenant, the landlord must follow the eviction process set out in the law (starting with step 3 below).

As of 2025, no state allows a landlord to use self-help eviction measures to remove the tenant, like changing the locks, removing doors, shutting off utilities, or removing the tenant’s personal property. However, despite such self-help tactics being illegal, they still happen regularly:

A 2020 National Housing Law Project survey of 100 legal aid and civil rights attorneys in 38 states found that 91% of legal aid organizations overall reported illegal evictions in their area, while “53% saw tenants being illegally locked out of their homes by landlords” and “18% saw tenants facing landlord intimidation and other eviction threats.” When NHLP conducted a similar survey in 2021 in the wake of the end of the federal moratorium on evictions, 35% reported a rise in illegal evictions.

In a 2021 Philadelphia report, “almost 6 percent of respondents who moved between February 2019 and February 2020 said it was because their landlord had locked them out.”

In a 2023 LSC brief on illegal evictions, “[legal services] providers reported that illegal evictions have been a steady source of housing instability for low-income families in their areas.”

According to 2024 Census data, over 200,000 households reported feeling pressure to move due to landlords using self-help tactics.

These numbers are very likely a dramatic understatement of the problem, as illegal evictions are very difficult to track.

ADVOCACY TIP

Self-help tactics get used because they are faster, cheaper, and simpler. Tenants might not know these tactics are illegal because few tenants have a lawyer, meaning there’s a good chance that landlords who do these things will not be caught. Tenant rights education should include information about whether a tenant can be told to leave before a court action is finalized. In addition, an important part of advocacy is working with and persuading law enforcement officials to enforce laws that prohibit lockout.

Step 3: The landlord begins the eviction process by serving notice to the tenant.

Before a landlord can file for eviction in court, virtually all states require the landlord to provide a notice to the tenant stating the reason the landlord wants to evict the tenant. The notice also gives the tenant a certain amount of time (which is set by law) to either fix (“cure”) the issue mentioned or move out. The most common reason involves non-payment of rent. Other than non-payment of rent, the landlord may file for eviction based on an alleged violation of lease term. What constitutes a “breach of lease” depends on state law, but can include criminal activity, nuisance activity (like disturbing neighbors with loud noise), damage to the property, or having an “unauthorized” occupant.

Another reason a landlord might want to evict a tenant is because a landlord has decided not to renew the lease. As shown in the LSC Eviction Laws Database, most states do not require that the landlord have a “just cause” (i.e. reason) to end a tenancy at the end of the lease term; they can just decide not to renew.

Once the tenant receives the notice, they might move before the landlord takes the next step and files in court. They might want to leave, are afraid of the eviction court process, are offered money by the landlord in exchange for moving (called “cash for keys”), and/or don’t know they may have a defense to the eviction. When a tenant moves after getting this notice but before the court process, it’s called an informal eviction. As with self-help evictions, it’s difficult to know how often informal evictions take place because they happen outside of court and without record-keeping. But a 2015 study in Milwaukee found that 34% of tenants who received an eviction notice moved without going to court.

It has been estimated that the combination of illegal and informal evictions add up to more than five times as many evictions as those filed in court.

Step 4: The landlord files in court for eviction.

If the tenant has received the notice but has not moved out or fixed the problem in the time allowed, the landlord can file a complaint or petition in court that is then served on the tenant. A 2021 Legal Services Corporation (LSC) report looking at eviction laws around the country found an unreasonably short amount of time in a great many jurisdictions between the tenant being served with eviction papers and the court hearing: in 39 of the 56 states and territories that the LSC studied, the time between serving the eviction summons on the tenant and the eviction hearing was “– a range of only 2-13 days …For most tenants, particularly those who are low-income, this is not enough time to seek legal counsel or advice, take time off from work, obtain childcare, or arrange transportation to and from the courthouse.” Additionally, filing an eviction is often very cheap: the LSC report found that “[a]s of January 2021, 22 states/territories set minimum eviction filing fees below $100, 12 of which are below $50; 24 states/territories do not have laws establishing a base filing fee, leaving local jurisdictions to set their own fees with no minimum.” When evictions are this cheap, there is not much incentive for a landlord to try to work out the problem with the tenant instead of going to court.

Court papers can be difficult to understand, especially for tenants who do not have a legal background or where the court papers aren’t in the tenant’s primary language. In addition, as shown in the LSC’s Eviction Laws Database, only 6 states (as of 2021) required the court summons to include information about “eviction related services” that could help the tenant.

Depending on federal, state, and local law, there is a wide range of defenses and counterclaims that a tenant could raise:

Depending on the type of housing (public or private) and the jurisdiction where the eviction is taking place, a tenant may have defenses related to the landlord failing to follow the right steps related to the eviction papers served on the tenant (often called “procedural errors”). For example, a landlord may not have provided enough notice to the tenant or failed to include documents along with the filing in court that the law requires. In other cases, a landlord may have had someone file the eviction who was not allowed to do so.

In other cases, the tenant may have “substantive defenses”. These can be things like the landlord failing to account for all the rent paid by the tenant, invalid lease provisions (like provisions that state or local laws say can’t be in a lease), or violations of the landlord’s duty to keep the home safe (known as the “warranty of habitability”).

In many jurisdictions, once the complaint is filed, the tenant loses the legal right to fix the reason for the eviction (“right to cure”), such as by paying the rent owed, but there are exceptions: for instance, Georgia law as of 2025 allows a tenant to pay the full rent plus certain costs up to 7 days after the eviction filing and it serves as a complete defense to the eviction.

Even when these errors are clear, landlords are often still able to get a judgment unless the tenant recognizes and raises these issues because judges themselves are unlikely to call out those errors. In a 2021 study of evictions in Virginia, the authors found “significant variation” in whether the court checked for technical issues: “In Richmond, for example, judges checked notices for legal sufficiency in 40% of all hearings, and ensured that the defendant was properly served with a summons in almost half of all cases. This was notable compared to other jurisdictions where this happened in fewer than a fifth of all hearings.”

ADVOCACY TIP

Push for state laws that lengthen the amount of time a tenant has to respond to an eviction notice or the amount of time between the eviction filing and court hearing. Lengthier times give attorneys more of a chance to connect with tenants and provide meaningful legal assistance.

Step 5: The court hearing occurs.

At some point after the tenant is served with the eviction papers, a court hearing will be held. Some state laws specify that an eviction hearing must occur within a certain number of days of the eviction filing, which will make the hearing happen more quickly.

If a tenant does not appear for the hearing, the court will typically enter a default judgment in favor of the landlord, so long as the landlord has appeared in court. But default can also happen in more ways than just not appearing in court. In 19 states, if the tenant fails to file a written answer to the eviction complaint before the court appearance date, that can lead to a default as well.

If the tenant does not default, on the date of the hearing a tenant’s case is likely one of many. In Philadelphia, an eviction “session” could have up to 100 cases and in New Jersey a court could see 200-300 cases a day.

To get through the cases on their docket quickly, judges may strongly encourage or require the tenant to negotiate with the landlord or the landlord’s agent/attorney before speaking with the judge or presenting any evidence, even if the landlord may have failed to file the eviction properly. For example, in Philadelphia:

“The Trial Commissioner reads aloud a prepared statement about noncompliance, which informs the parties that court practice requires them to try to reach an agreement before resolving the particular issues of noncompliance. In other words, before the parties negotiate [an eviction judgment], the landlord does not have to present documents that may have been missing in the original filing, nor does the court adjust the complaint amount to remove any monetary amounts requested for periods during which the landlord did not have the required documents. The rationale for this practice is that focusing on noncompliance issues could make the parties less amenable to negotiation. The result is that in some cases, as identified in our analysis of agreement amounts, some tenants may agree to pay amounts they do not technically owe under the law.” (Reinvestment Fund, 2020, p. 8-9. Note that the “prepared statement” or “non-compliance script” the Trial Commissioner reads aloud is included in the analysis as Appendix B, pages 23-24.)

If the parties don’t settle and the court holds a hearing, it is rarely a full trial. In fact, eviction hearings are typically incredibly short. For instance, in Cleveland, one study found that “the average case lasted three minutes and 21 seconds,” and increased to about “5 minutes and 54 seconds” if the tenant was in court. In a study of evictions in Virginia, “...in the summer of 2021, more than 40% of all hearings lasted less than one minute, and fewer than 5% lasted more than ten minutes.” During these “hearings,” judges might not answer questions from the tenant or even permit them to speak.

The Dallas Morning News gave an example of one such case:

Judges became irritated by defendants’ courtroom decorum and made it explicitly clear that the plaintiffs’ presentation swayed their judgment. One judge became so incensed by a defendant who blurted out a plea for help and a complaint about missing work that he volunteered legal advice to the plaintiff.

“I’m missing work to be here, please work with me,” pleaded the defendant in that case.

“Sh.. sh...sh... be quiet, be quiet, you gotta be quiet when I’m speaking,” said the judge, before turning to the plaintiff’s lawyer and adding: “Take the rent! Take the money and you can still evict them. Even if you accept the money, they can be evicted.”

Step 6: The court issues its decision.

If the landlord and tenant haven’t reached a settlement before the end of the hearing / trial, the court will may decisions about:

whether the tenant can stay or must move out,

whether the tenant must pay money to the landlord, and if so, how much,

any applicable dates (the date the tenant has to move out by, or the date when an eviction warrant will be executed if the tenant has not moved out), and

whether the eviction will appear on the tenant’s record. In some jurisdictions the eviction record may be “sealed”, meaning it will not turn up in databases that landlords search when screening potential tenants. In such jurisdictions, sealing either happens automatically or the tenant has to ask for it and the judge decides whether to do so. In some places it may be possible for the landlord and tenant to come to an agreement where the eviction case is dismissed in exchange for the tenant moving out, meaning there will be no eviction record.

If a tenant appeals the court’s decision, they may be required to put up an “appeal bond” equal to a certain amount of money, often equal to the rent the landlord says the tenant owes.

Step 7: The landlord recovers the unit.

If the eviction is granted, the landlord has the right to obtain a warrant of execution that empowers them to take back the unit. Once the landlord obtains the warrant, they have a period of time during which they can have law enforcement carry it out. If the tenant has not moved out, law enforcement may physically remove both the tenant and their belongings from the unit, and the belongings may wind up on the street.

The Aftermath and Consequences of Eviction

An eviction doesn’t just remove a tenant from their home: it devastates many areas of their life while also disrupting the fabric of whole neighborhoods and communities.

Evictions can lead to housing instability and homelessness, which comes with additional issues. Many tenants cannot find a new place to move to quickly, and may experience periods of extreme housing stability or homelessness if they have to stay at a shelter, sleep in their vehicle, or double up with family or friends. If they do not have those options, some people have to resort to sleeping on the street, where they can risk arrest, incarceration, prosecution, and creation of a criminal record. Even when an evicted tenant finds replacement housing, their new housing conditions are likely to be worse.

Even the threat of evictions can damage physical and mental health. A 2017 research review “revealed a general consensus that individuals under threat of eviction present negative health outcomes, both mental (e.g. depression, anxiety, psychological distress, and suicides) and physical (poor self-reported health, high blood pressure and child maltreatment).”

Evictions deeply affect the lives of children. Children under the age of five are the population most at risk of eviction, and “...the risk is acute for Black children and their mothers, ages 20 to 35. In a given year, about a quarter of Black children under 5 in rental homes live in a household facing an eviction filing.” Though not looking at evictions specifically, a study looking at tenants who fell behind on rent, moved multiple times, and/or experienced homelessness found that “[as] compared with children in stable housing, children in households behind on rent had increased adjusted odds of lifetime hospitalizations…and fair and/or poor child health.” An eviction that results in a move can impact a child’s education by affecting the child’s ability to concentrate in school as well as attend school. Evictions have been linked to increased school absenteeism: in one Cleveland study, there was an increase in school days absent during the year of filing both if there was just a filing and for cases with a move-out order. There are also significant health consequences for children, especially if they experience homelessness.

Evictions can be part of or lead to other civil legal problems. The Legal Service Corporation’s Justice Gap report found that 81% of households dealing with eviction experienced at least 5 additional civil legal problems, compared to 39% of all households studied.

Evictions have a steep financial impact. Not only might a tenant have to pay the landlord’s attorney fees and court costs, but the tenant may lose their job if they are unable to get to work from wherever they move to. Both the fees/costs and loss of employment may make them unable to pay the security deposit and rent for a new home. If the eviction judgment also requires the tenant to pay money to the landlord, that money judgment can be reported to credit agencies and significantly lower tenants’ credit scores. Money judgments can also be sent to collection agencies. In addition, tenants are at risk of losing personal possessions such as furniture and may have real difficulty in getting replacements.

Even if a tenant wins an eviction case, the stain of the case is very hard to remove. Landlords view tenant credit reports and rely on them to deny tenants housing, and these reports can follow tenants for a long time (which is why evictions are referred to as the “Scarlet E”). The mere filing of an eviction case against a tenant can lead to a negative rental history for the tenant, regardless of the outcome. Some states have eviction record-sealing laws so that landlords cannot see eviction filings when deciding whether to rent to a tenant,, but even in those states, tenants need to understand these laws exist and how to use them. In addition, eviction records can be inaccurate or incomplete.

-

Resources

-

Return to